Lewis Hamilton went into Formula 1’s summer break on his strongest run of form of the season, and his most successful spell in this rules era entirely, despite a lingering clash between his driving style and this generation of car.

The current ground-effect era is one Hamilton really dislikes, at least in terms of what it asks of a driver in qualifying, and has not brought the best out of him.

For the first time, F1’s most successful driver ever is struggling to adapt to the demands of his machinery. At his most honest and self-critical, Hamilton has claimed he’s “sucked” in qualifying for a long time, and that he finds this generation of F1 car “really frustrating” to drive.

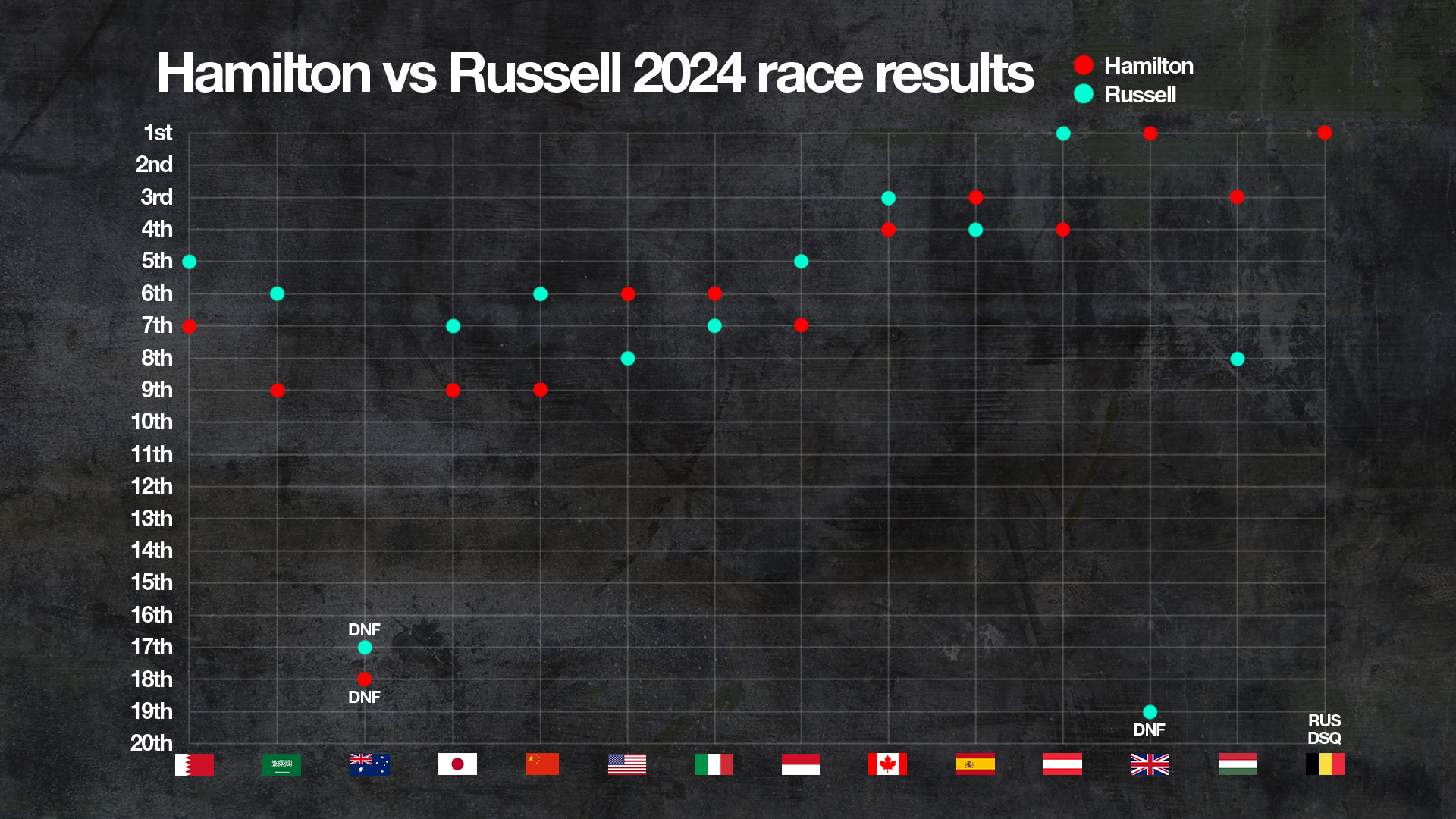

And yet, the pre-August formbook would suggest otherwise. Having ended a victory drought of almost three years in the British Grand Prix, Hamilton won again in Belgium – in slightly strange circumstances, having been beaten on the road by team-mate George Russell’s unorthodox strategy before he got the win ‘back’ when Russell was disqualified for being underweight.

Hamilton’s run of four podiums in five races have, combined with Russell having a DNF and a DSQ in that time, jumped him ahead of his team-mate in the championship standings and put him in contention for a top-three finish, something that would have looked utterly unattainable earlier in the year.

There’s a contradiction in the way Hamilton struggles in a car that responds best to a style of driving he hates, yet lately looks as strong as ever – mainly on Sundays.

Even though he’s outqualified Russell three times in the last five events, Russell is beating him 10-4 on head-to-head form. And while Hamilton’s bleak prediction back in May that he wouldn’t outqualify Russell at all for the rest of 2024 hasn’t quite come to pass, the trend is clear: Russell’s faster over one lap.

THE DRIVING STYLE CLASH

Hamilton’s admission of a driving style incompatibility is one of the most intriguing developments of this season. The current cars are the biggest and heaviest cars they’ve ever been and everything about them – the aero, the weight, the mechanical platform and the tyres – has essentially exacerbated some anti-Hamilton characteristics.

It’s easy for these cars to exist on a knife-edge between chronic understeer, when it is difficult to get the rear rotated, and sudden instability, as the aero balance shifts forwards dramatically on these cars as the speed reduces which can trigger small slides that spike tyre temperatures.

Slow corners are generally where the real laptime gains are to be found, and Hamilton has usually excelled at finding them. But F1’s modern ground-effect era isn’t letting that come naturally.

It doesn’t reward braking late with a sharp rotation deeper into the corner, in what is commonly referred to as ‘V-ing’ the corner off. Instead, these cars prefer a gentler, steadier cornering approach, by braking a little earlier and rolling the speed through the corner, making it more of a U shape.

This is what Hamilton says he “hates”.

“That’s just not me,” he said at the Hungarian Grand Prix when asked by The Race about this unique problem faced in his career for probably the first time. And as Mercedes trackside engineering director Andrew Shovlin explains, it’s not a 2024 phenomenon. Hamilton has struggled with this whole generation of car not suiting his style.

“It’s particularly that he struggled on the single lap,” says Shovlin.

“It’s more just the way that he wants to attack a corner. When you do that, then the car would snap to oversteer. You start to build tyre temperature.

“Most of our work has been trying to give him a car that you can drive with the very attacking style, extract the lap time out of it without it just sort of breaking away on the way in and catching him by surprise.”

Shovlin’s been part of every single Hamilton win and title with Mercedes so he knows the seven-time world champion’s skillset better than almost anybody in the paddock.

When The Race revisited every single qualifying performance so far, reviewed onboard footage and compared telemetry between Hamilton and Russell, two distinctly different approaches from the two drivers became apparent.

Russell brakes fractionally earlier, but starts turning much later, and carries more speed through the corner and exiting it. Whereas Hamilton brakes later, but starts turning in earlier.

This loads up the car more gently, which could be a sign that Hamilton’s wary of the rear stepping out if he turns in too aggressively – but it’s also consistent with making the entry narrower and then trying to have a sharper rotation.

The different approaches mean Hamilton’s entry to the corner is tighter, so while he gets closer to the geometric apex, his minimum speed drops lower and he still has more lock on through the corner, delaying getting back on the power.

There are multiple examples throughout the season – Bahrain, Australia, China, Imola, Canada – where Hamilton has lost upwards of a tenth of a second through individual corners in qualifying.

Sometimes this has resulted in a slightly inflated gap to Russell, but at its worst it has even been the cause of Hamilton getting knocked out of qualifying early.

WHAT’S CHANGED?

Interestingly, there are far fewer recent examples of this being a significant loss. Hamilton has typically been very good in very different cars, after all, so sooner or later he was bound to mitigate the worst of his issues.

But Hamilton’s way of driving is deeply ingrained in him and unpicking that at 39 years old, nearly 20 years into driving F1 cars, is not going to happen. He’s even joked that he’s “stubborn” so “I just keep trying to drive the way I want to drive!”.

So, Hamilton’s driving style hasn’t become drastically different of late, although he seems to be showing a little more restraint in how he attacks the corners, and he’s not asking things of the car that it cannot handle because he’s not overreaching.

This has eliminated the worst of the oscillations in his qualifying performances and made Hamilton a consistently better qualifier as the year has progressed.

Perhaps the biggest factor is how Mercedes has improved its car. Various changes to the floor and just as importantly the front wing have helped turn Mercedes’ season around, from being nowhere in the early races to winning three of the four grands prix before the summer break.

The developments have given the car a better balance at high speed and low speed, and more downforce. It’s become easier to set up, more predictable, and the drivers can attack with more confidence. Hamilton’s had a bigger relative gain from this.

“Early on, perhaps Lewis was finding that the car more difficult to deal with,” Shovlin says.

“One of the areas that we’ve improved with the car is being able to land the setup in FP1 that’s a good foundation to start building on performance and fine tuning it. That helps your weekend enormously.

“In the early part of the year, we were making relatively small changes, and suddenly the whole car balance left us, and we were really struggling.

“So that certainly helped. And yeah, it’s probably fair to say that in the earlier races, Lewis was finding it more difficult to set up than George.”

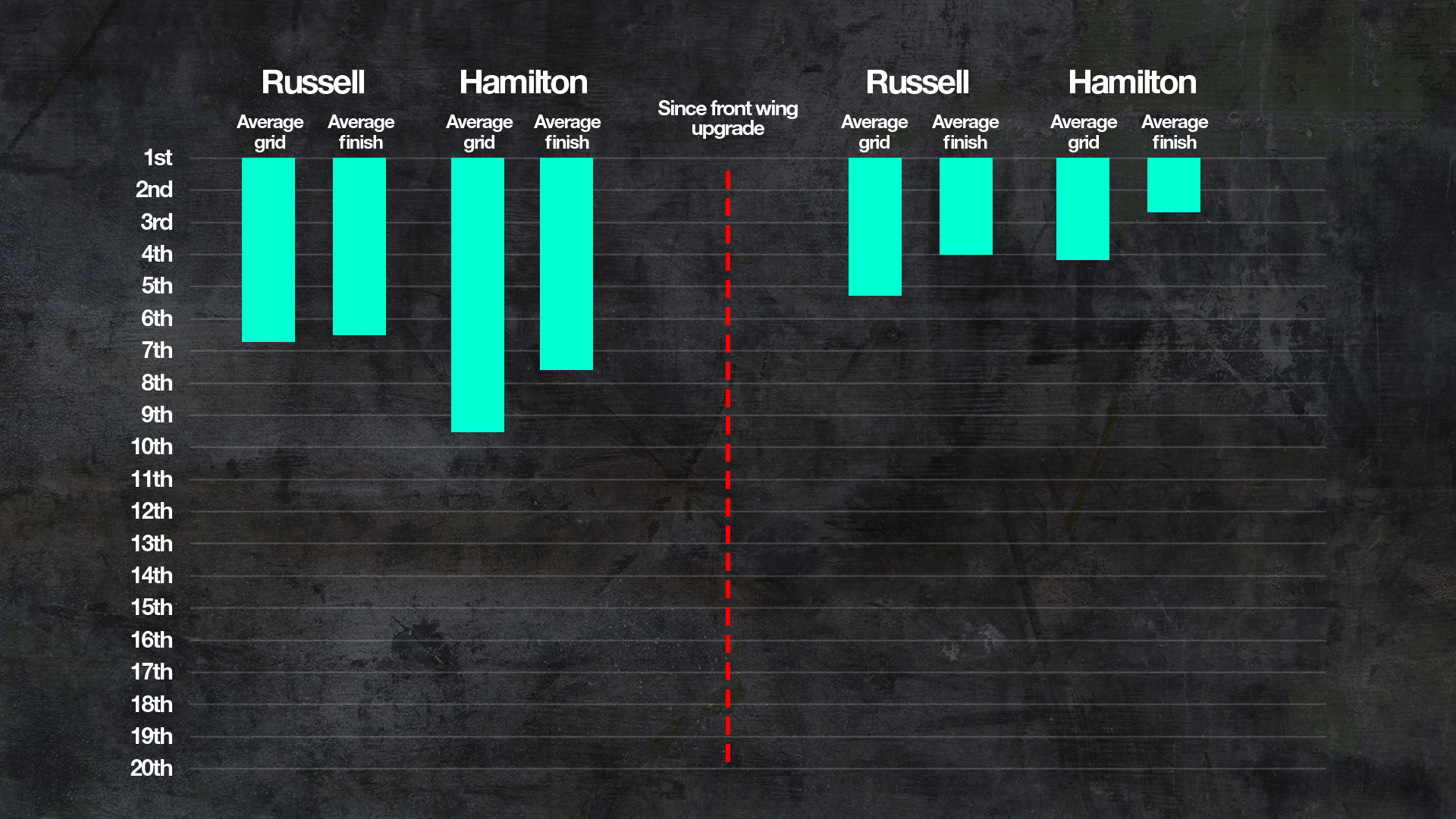

Before getting the new front wing that came in the middle of a run of updates halfway through the season so far, Hamilton’s average grid position was a meagre 9.5 and his average finishing position was 7.6 – but since he first used the new front wing in Canada his grid average is down to 4.17, and his average finishing position is 2.67.

That is a lot less disastrous than made out by the prevailing narrative just a few races ago. And it has helped bring down the overall 2024 comparison too.

The margins have been super tight and while the head-to-head numbers make for bad reading for Hamilton, he is rarely being blown out of the water. He’s qualifying just over a place behind Russell on average and matching his average finishing position.

In terms of deficit, when assessing the most relevant sessions (which means discounting China, Hungary and Belgium because of a mix of unrepresentative laptime for different reasons), Hamilton’s looking at a deficit of 0.13% – or just over a tenth. And that’s when discounting two of the four times Hamilton’s outqualified Russell.

As Hamilton puts it: “not a disaster, it’s just above average”. Which, given his sky-high standards, is not as spectacular as we’ve all become accustomed to.

AVOIDING A RICCIARDO TRAP

While it still means something that Hamilton’s been on the wrong side of fine margins more often than Russell has, the obvious silver lining (apart from the recent qualifying improvement anyway) is the quality of the Sunday work.

His race pace, his judgement and his tyre management are still top tier. And he remains one of the very best in wet conditions too. It’s just that the ‘wow’ moments on Saturday are few and far between, to the point of being almost non-existent so far this year.

The fact that Hamilton’s tried to keep driving the way he wants to, even though it doesn’t always work, helps explain the peaks and troughs. It depends whether the car/tyres/conditions can support his technique or not on a given lap.

Even early in the season there was evidence of Hamilton being faster than Russell through some slow corners, if the car could handle what he was asking of it.

“It doesn’t always work,” Hamilton admits. “And I’m trying to massage my way through.

“Ultimately, as a driver, you have to be adaptive. You have to concede that sometimes your approaches to certain things aren’t perfect, and you just start looking at ways in which you can still hold on to the essence of what made you as good as you’ve been, and see how you can evolve that.”

A contrast would be Daniel Ricciardo, who encountered the bizarre McLaren car characteristics in 2021 and 2022 and was encouraged by the team to reconfigure his driving technique to replicate what Lando Norris was doing.

That should have unlocked a higher peak. But Ricciardo was never able to adapt to driving ‘the McLaren way’ naturally. It became extremely disjointed, and he probably struggled worse than if he’d cracked on with his own methods even if they didn’t gel perfectly with the cars.

Hamilton hasn’t gone down that route, even though he and Russell and the team have inevitably experimented with set-ups and small style tweaks as a collective. That’s just how a good team and good team-mates operate, learning from each other all the time.

He’s probably better off for being stubborn now he’s seemingly come through the worst of it. As the car’s got better and given him a little more confidence, Hamilton has upped his game, and perhaps shown a little more restraint by not over-driving while trying to pull a rabbit out of the hat like in the past.

It has made Hamilton a consistently better qualifier as the year has progressed, and a bigger threat in the races as a result. He still doesn’t enjoy what F1’s current cars demand, and he may never click with this era like he has past ones, but Hamilton’s recent form shows he and Mercedes can at least mitigate the worst of any incompatibility to good effect.